wading through the ruins of childhood empires

by mina tobya

We were hoping for a time capsule. Expecting one, even, when we stepped into our old apartment in Beirut. It had traded hands from one member of my family to the next for the past 15 years we’d been away, but somehow we thought nothing would change.

Of course, everything does.

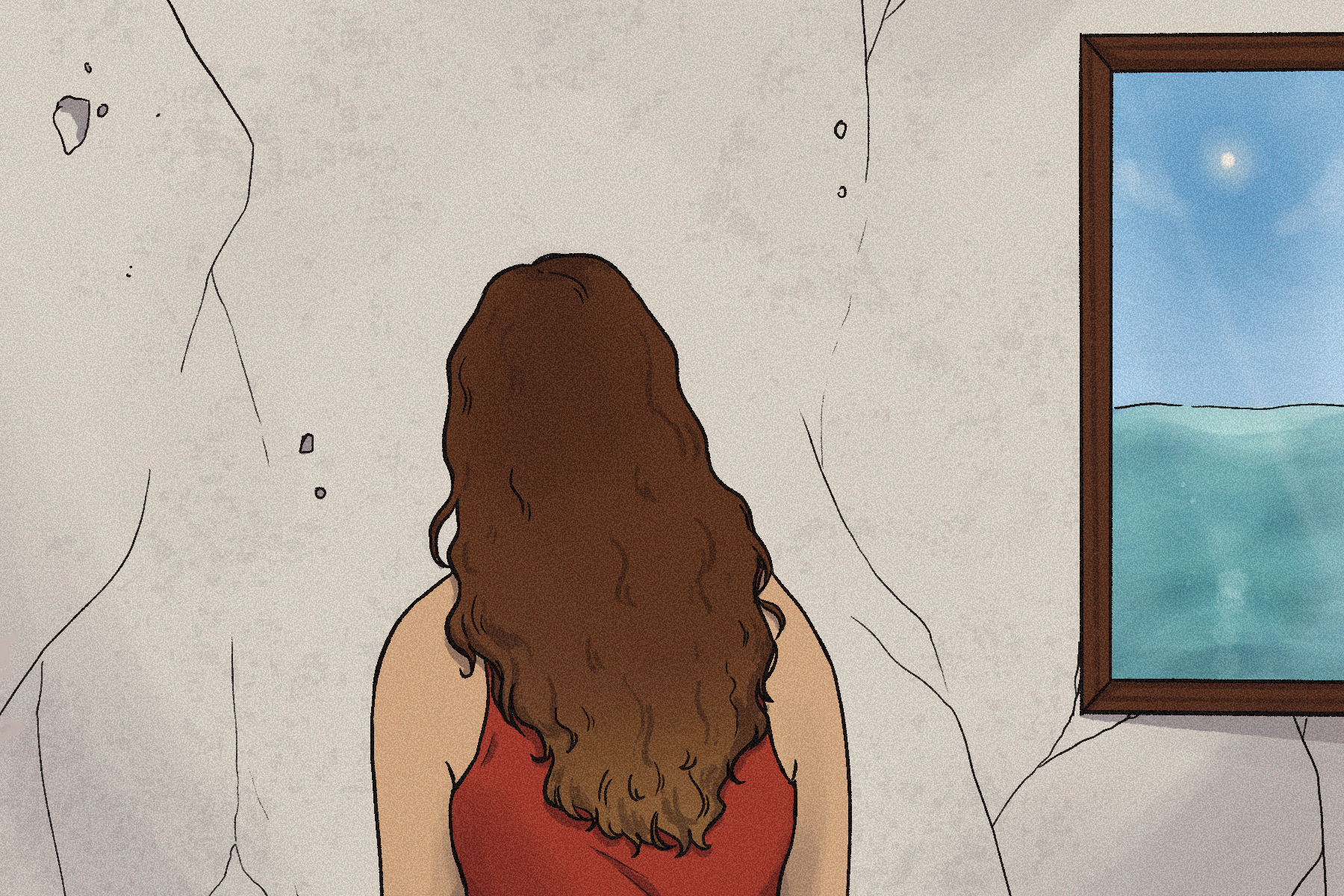

But, this place that used to be our home hadn’t just changed; it had deteriorated without us. Now empty and abandoned in the middle of construction project after construction project, nothing remained but dust. The walls of my old bedroom turned bare, the floors ripped out and never replaced. The terrace looking out to the Mediterranean paved over, cutting off our sight of the horizon. Our cozy old furniture nowhere to be found, replaced by scarce pieces we held no connection to.

There’s a unique disorientation in walking through the halls of your home and not recognizing it. Taking every step knowing the floors don’t remember the weight of your feet. I was a new person. This place and this country didn’t recognize me as we greeted each other for the first time in too long to remember.

They probably searched for a bright-eyed, two-foot tall girl in clothes her mother picked out, speaking what few words she knew through her missing baby teeth. They must not have recognized the woman they saw, talking at a mile a minute in a language they had never learned — and with all her grown-up teeth, no less. We couldn’t have picked each other out in a crowd, which means we couldn’t give each other a warm embrace when we came back together.

More than a time capsule, I think I was hoping for a time machine. I didn’t want to sit and stare at my nostalgia, I wanted to be able to transport myself back 15 years and greet the walls with my baby-teeth like I hadn’t been away at all. But, time has given me too much since then to be able to take it back.

So, we sat and picked at the scabs of our grief. My grandmother lamented the loss of the beautiful home she’d built while she stood in the middle of it. She sifted through old photographs and told me stories of the people in them. Black and white pictures of her and my grandfather at the center of a packed dinner table, a cigarette in her hand and a smile on his face. A business meeting where they talked about things that don’t matter now, debated decisions that have long-since been made. Some people, she didn’t know. Those photos, she threw away or ripped up without a second thought.

I’d grab her trash, neatly place them in an envelope and stow them away so I could imagine their stories myself. They’re stories of happy lives back where ours started. I kept a photo of my mother’s car rolling out of the driveway in Baghdad, despite my Teta’s protests that it wasn’t worth anything. I don’t think she’s right.

At a certain point, when something has been gone long enough, a simple memento turns into a historical artifact. People hang stone slabs in museums despite their inscriptions being receipts or mundane complaints, but because they’re the only remnants of long gone empires people come to see them. They see value in them. This photo is an imprint of a long gone family empire and the only thing left of it was the dust all around us. We were standing on the ruins.

Around these ruins, the world still turned. To the old neighbors who came to visit, it was just another day in the same land they’d been in since yesterday, and the day before that, and the year before that. Their homes still looked and felt like home to them, never abandoned or left sitting lonely and hollow. Life never stopped bouncing off their walls like it did ours. We were the anomaly — some remnants of a long-lost era now distinctly out of place.

I spent those weeks feeling like a puzzle from the wrong set trying to find where I fit. For the first time, I was confronted with what my home really is. A home is what shapes you — your values, your instincts, your interests — and I had been shaped by America. I spoke English more strongly than Arabic, I knew American states instead of Lebanese regions. I like lattes more than Turkish coffee, I want to live on my own instead of in my family’s house. At every turn, these factors clashed with my being Middle Eastern in the Middle East. To everyone who had grown up there and never left, I was an American tourist.

Baristas at coffee shops couldn’t understand my Iraqi accent, I had to learn the verbiage of the Lebanese dialect. They’d ask me where I was from, meaning: where had I grown up? Meaning: what identity claims you more than you can claim it? In America when people asked this question, I’d say I’m Middle Eastern. In the Middle East, I have to say I’m American. No one right answer, no solid place to call home, just a variable response.

It changes how people see you. In the States, when I tell people I was born in Iraq, that my grandma is Lebanese, that Arabic is my first language, there’s a look behind people’s eyes — something like pity. In my head, they’re thinking “it’s so great you got out, that place is full of heartache.” I know why they’d think that, it’s not like we get the best press. But, in Lebanon when I tell people that I’m back to visit from America, there’s a look of recognition — a warm welcome home, something like “I’m sorry you had to miss this.”

I’ve missed a lot.

I’ve missed the scent of the saltwater on the coast, the finest sand I’ve ever felt on my skin. I miss the air in the mountains and the excessive business of the streets. I’ve missed seeing a picture of Saint Charbel in every house I enter and climbing the steps of Harissa on her hilltop.

I’ve missed my family.

My great aunt Nada is perhaps the biggest reason I wanted to go back to Lebanon. I hadn’t seen her since I was 6 years old, but I remember her jokes and her warm hugs and her booming laughter. She’s always looked just like my Teta — the older sister she hadn’t seen in 20 years. When they saw each other again, they didn’t look like twins anymore. Nada’s face had tanned and wrinkled differently from Teta’s, she kept her hair long and dyed while my Teta cut hers short. The years had worn on them, and maybe the distance had, too.

Her grandson — my cousin Crís — is now the age I was when she last saw me. He spent our entire visit running around the apartment, causing trouble and playing video games on his dad’s phone. He roped my sisters and I into soccer on the balcony and pranks on the elders. He has Nada’s spirit.

She loves to poke fun and find the joy in every little thing. Her hugs had gotten warmer, if that was even possible. I stood and watched her steep the Turkish coffee in her old iron pot, ashamed at how long it had taken me to get back to her. I was even more ashamed when we went to visit my great-aunt Marie, their oldest sister, because I hadn’t remembered her at all. I don’t think she remembered me, either, but I can’t blame her. Still, she took care of me when I got sick. She tucked me into bed and sang me a song I don’t know the words to, held my hand in the dark. I wondered if she did that for Teta when they were girls.

In her house, we found another artifact from a past life in Lebanon: a photograph of Teta and Marie laughing in the kitchen, no older than 30. Her kitchen looked the same, but nothing else did. Not the brightness of their smiles or the smoothness of their skin, not the closeness that was always at their fingertips back then.

Seeing those three together, gathered around an old view master and passing it between them, I couldn’t help but think of my sisters. I could see us in them. I saw more of us in them as they started to bicker and argue, Teta getting defensive when Nada’s jokes hit a little too close to home and Marie trying to keep the peace. They cried when they said goodbye, knowing it would likely be the last time they saw one another in person. The last time my grandmother would see home.

When we left, Crís asked me when we’d be back to play with him again. I didn’t know what to tell him. I didn’t want to tell him he could be too old to play games by the time we saw each other again.

Things are so different now. Lebanon is different. I am different. In my head, Beirut was a magical place, but being there reminded me that it’s fallible. It’s a place where the banks can’t be trusted so everyone relies on cash, and the value of the Lyra has gone down so much that people trade in American dollars. It’s a place where my grandmother would only let me drink bottled water because the tap would make me sicker. It’s a place where traffic on the autostrat requires a driving course all its own, and a courage to flip people off that I just don’t have. I’m grateful that my family brought me back, god knows they have the courage.

I’m also grateful to have something to go back to at the end of this. Almost the entire trip to Lebanon, my sisters and I couldn’t wait to go back home to Michigan. We missed our friends, our jobs, our carefully curated bedrooms and cities we knew like the backs of our hands. None of those things were in Lebanon, no matter how much I had spent my life aching to see it again. I don’t know how to not feel guilty about that. Maybe I always will, but it’s an ache I can live with. That ache reminds me of home — all my versions of it, even the ones long lost to time.

by mina tobya

edited by erin evans

design by matthew prock